It’s “carnival” season again – a weeks-long (n some countries, a months-long) celebration developed in response to the religious observance of Lent, which (according to Wikipedia) is “a 40-day period of preparation of the believer through prayer, doing penance, mortifying the flesh, repentance of sins, almsgiving, and self-denial. This event is observed in the Anglican, Eastern Orthodox, Lutheran, Methodist, and Roman Catholic Churches.”

Unfortunately, this “response to Lent” called “carnival” is nothing more than an excuse for people to allow themselves to be ruled by their deepest, darkest, most uninhibited and decadent desires where “anything goes” before entering that period of repentance. A German friend of mine once told me that in Germany, where the season is called “Fasching” was created because “God LOVES to forgive! The more we sin, the more reason He has to forgive us,” my friend told me. (In other words, people who engage in this debauchery have NO clue about God and His Word!)

Carnival’s exact origins are unknown. In pre-Christian times, carnival celebrations symbolized the driving out of winter and all of its evil spirits (hence the masks, to "scare" away these spirits). But in the Middle Ages when Christians endured many trying religious disciplines during Lent, they celebrated “one last fling” in the week before Lent began, to help “offset the hardships” of Lent.

Mardi Gras – or “Fat Tuesday” - is the biggest day of celebration, and the date it falls on moves around. Fat Tuesday can be any Tuesday between Feb. 3 and March 9; but carnival celebration starts on Jan. 6, the Twelfth Night (feast of Epiphany), and picks up speed through midnight on Fat Tuesday, the day before Ash Wednesday.

According to a Wikipedia article “excessive consumption of alcohol, meat, and other foods proscribed during Lent is extremely common. Other common features of carnival include mock battles such as food fights; social satire and mockery of authorities; the grotesque body displaying exaggerated features, especially large noses, bellies, mouths, and phalli, or elements of animal bodies; abusive language and degrading acts; depictions of disease and gleeful death; and a general reversal of everyday rules and norms.”

In certain parts of Germany, “Weiberfastnacht” is part of the Fasching scene. Held in the Rhineland on the Thursday before Ash Wednesday. the day begins with women storming into and symbolically taking over city hall. Then, women throughout the day snip off men's ties and kiss any man who passes their way. The day ends with people going to local venues and bars in costume.

Here is an overview of the history of carnival (borrowed from The Free Dictionary by Farlex).

Since early times carnivals have been accompanied by parades, masquerades, pageants, and other forms of revelry that had their origins in pre-Christian pagan rites, particularly fertility rites that were connected with the coming of spring and the rebirth of vegetation. One of the first recorded instances of an annual spring festival is the festival of Osiris in Egypt; it commemorated the renewal of life brought about by the yearly flooding of the Nile.

In Athens, during the 6th cent. B.C., a yearly celebration in honor of the god Dionysus was the first recorded instance of the use of a float. It was during the Roman Empire that carnivals reached an unparalleled peak of civil disorder and licentiousness. The major Roman carnivals were the Bacchanalia, the Saturnalia, and the Lupercalia. In Europe the tradition of spring fertility celebrations persisted well into Christian times, where carnivals reached their peak during the 14th and 15th centuries.

Because carnivals are deeply rooted in pagan superstitions and the folklore of Europe, the Roman Catholic Church was unable to stamp them out and finally accepted many of them as part of church activity. The immediate consequence of church influence may be seen in the medieval Feast of Fools, which included a mock Mass and a blasphemous impersonation of church officials. Eventually, however, the power of the church made itself felt, and the carnival was stripped of its most offending elements. The church succeeded in dominating the activities of the carnivals, and eventually they became directly related to the coming of Lent.

Symbols and Customs

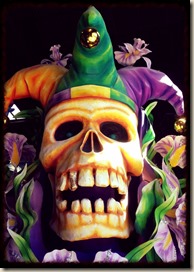

Although Carnival celebrations vary from country to country and region to region, they usually include some or all of the following customs and symbols. Most Carnivals offer participants various opportunities to take to the streets in costumes or masks. As people temporarily take on the identity represented by the costume or mask, they engage in a spontaneous kind of play-acting with other costumed participants and onlookers. The fool or clown plays an important role in many Carnival festivals and symbolizes the topsy-turvy nature of the holiday.

Many celebrations also feature a mock king and queen, who rule over the kingdom of Carnival during the few days of its duration. Some festivals schedule a symbolic funeral at the end of the week's festivities. A dummy, or some insignificant item, such as a sardine, is "killed" and buried, and this burial represents the death and laying to rest of Carnival for another year. Often people throw things at one another during Carnival celebrations, whether it be water, flowers, candy, oranges, or party favors, such as confetti or beads. Finally, Carnival customs often encourage people to eat and drink heartily, and may also include some loosening of the usual rules of social conduct.

Carnival in the Modern Era

In the sixteenth century well-to-do Italians began to host costume balls in celebration of Carnival. This trend eventually spread to other parts of Europe, giving rise to a courtly Carnival. This same trend led to the introduction of elegant floats and magnificent parades, which encouraged a more civil and structured celebration.

In spite of official opposition and unease, Carnival celebrations proved impossible to stamp out in much of southern Europe. In northern Europe, however, Carnival celebrations faded away in some regions where they had once been popular. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries people began to beautify the festival in response to new perspectives introduced by the Romantic movement, which tended to idealize old traditions and folkways.

Over time many Europeans discarded some of the dirtier and more aggressive customs associated with the holiday, such as throwing water or oranges at one another, and replaced them with gentler gestures, like tossing confetti and flowers. It became fashionable in some cities to ride in flower covered carriages, construct elaborate parade floats, and host elegant masked balls. As the parades grew in importance the nature of the festival changed. Previously everyone had participated in the masked hijinks. Now a division grew up between participants and spectators. In the past the spirit of Carnival swept over the entire town. Now it was concentrated along a specific parade route.

From Europe to the Americas

While some of these changes were felt in Spain and Portugal, their rural Carnival celebrations continued in the same rowdy spirit of ages past. People in the street threw oranges, lemons, eggs, flour, mud, straw, corncobs, beans or lupines (a type of flower) at one another, and people on balconies poured dirty water, glue or other obnoxious substances on the crowds below. Those in the streets battled one another with brooms or wooden spoons. Indoors people feasted on rich foods, to which they also treated guests. The wealthier homes might even toss cakes and pastries out windows to passersby. Colonists from these countries exported this version of Carnival, called Entrudo in Portuguese, and Antroido or Entroido in the Galician language of northwestern Spain, to Latin America.

Latin American Carnival celebrations blend European Carnival customs with African and Native American traditions of celebration. African-influenced music and dance, for example, play an especially important role in Carnival celebrations in Brazil and Trinidad. Meanwhile the French succeeded in transferring their Carnival celebrations to certain of their colonies in North America, namely those centered around the cities of New Orleans and Mobile. These celebrations, known as Mardi Gras, survive today, a regional American expression of an old European seasonal festival.

(Please check out these pictures from past carnivals, and skim the article called 12 of the best carnivals in the world to see for yourself the despicable, demonic, in-God’s-Face behavior that this sick anything-goes “holiday” exemplifies. It’s highly doubtful that YHWH “loves to forgive” this type of deliberate sinning! See our article about Deliberate Sin.)

No comments:

Post a Comment

All comments are moderated.